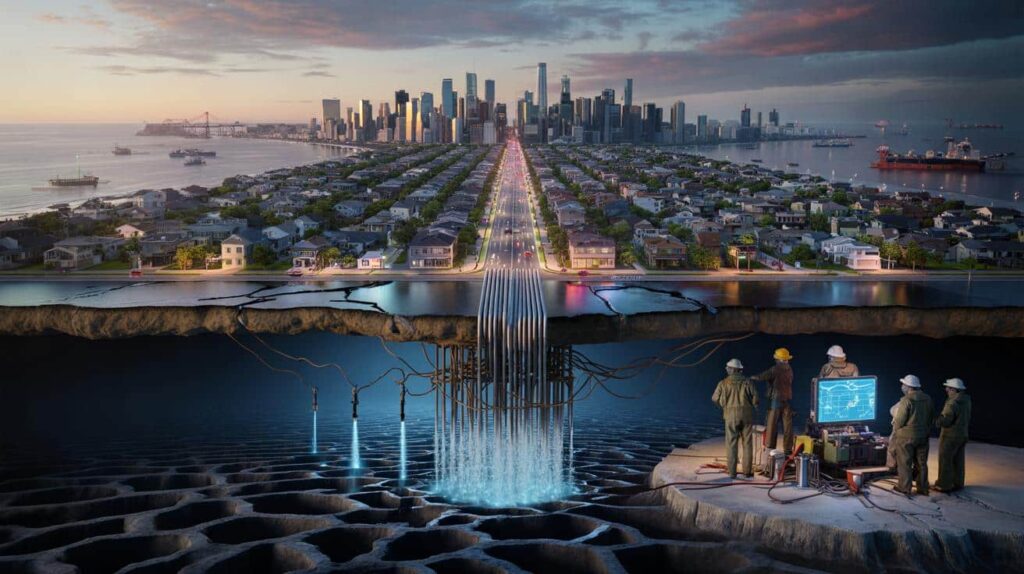

The first time you see the map, it doesn’t quite sink in. A cluster of famous skylines — Houston, Los Angeles, parts of Shanghai and Jakarta — perched above what engineers dryly call “depleted reservoirs.” You zoom in. Under the glass towers and endless suburbs: old oil fields, drilled and sucked nearly empty, now slowly collapsing under the weight of everything built on top.

Quietly, out of public view, some cities have been fighting back. Teams of engineers pumping water underground to prop up the earth itself, like slipping a jack under a car that’s already sagging.

The ground stops sinking so fast. The graphs look better. The headlines never appear.

But the question lingers, just under the concrete.

Did they buy time — or break trust?

When the ground under a city starts to fall

On a hot afternoon outside Houston, the sinking doesn’t look dramatic. The strip malls are open, the freeways humming, kids kicking soccer balls on fields laid over old rice farms. You’d never guess that, beneath the asphalt, the land has been slowly slumping for decades. A few inches here, a foot there, neighborhood by neighborhood.

Engineers have a painful name for it: subsidence. Land that once sat steady now creases and sags as oil, gas, and groundwater are pulled out. Pipes crack. Roads ripple. Floodwaters hang around longer than they should.

From street level, it just feels like the city being “weird” again. Underneath, the geometry of the ground is changing for good.

The basic physics are brutally simple. Pull fluid out of porous rock — oil, gas, or water — and the grains lose pressure and start to compact. Multiply that by decades of drilling under wide, flat cities built on soft sediment, and you get a slow-motion buckle.

In places like California’s Central Valley, the land has dropped more than 8 meters in a century. Parts of Mexico City have sunk over 30 feet since the early 1900s, buildings tilting like exhausted teeth. Some Asian megacities are now dropping by several centimeters a year.

So engineers began looking at a strange fix. If extraction caused the sinking, maybe putting something back could hold the ground up.

The idea sounds like sci‑fi but it’s textbook petroleum engineering: inject water into hollowed reservoirs to restore pressure and stabilize the rock. Oil companies have done it for decades to squeeze out the last drops of crude. This time, the target isn’t profit, it’s survival.

Cities sitting above aging oil fields started to ask: what if we used those same wells to support the surface, not just the industry? A controlled push from beneath, instead of one more pull.

It’s a delicate move. Add too little water and the land keeps sinking. Add too much and you risk micro‑quakes, leaks, or pushing contaminants into drinking aquifers. The stakes are nothing less than the stability of entire districts.

A quiet fix — and a loud ethical question

The method itself can be oddly mundane. Engineers use existing well networks, tie them into injection stations, and start sending treated water down thousands of meters into depleted formations. Pressures are monitored like ICU vitals — graphs, alarms, thresholds that must never be crossed.

Some water comes from wastewater plants, some from industrial runoff, some from brackish sources that no one wants to drink. It’s filtered, sometimes disinfected, sometimes mixed with corrosion inhibitors so it doesn’t destroy the pipes on the way down.

On the surface, the only signs might be a fenced pad, a humming pump, and a sign with a bland code name. “Reservoir Management Unit 7.” Nothing that screams: we’re literally holding up your neighborhood from beneath.

In one coastal city, engineers noticed something terrifying: tide gauges and GPS markers showed the port area dropping twice as fast as predicted. Warehouses sat on reclaimed land over an old oil field, once a bonanza, now an underground honeycomb.

A quiet task force convened. Within months, they’d re‑permitted old production wells as injection wells, mapped safe pressure limits, and started sending millions of gallons of water underground. Insurance executives were briefed. A few key politicians were looped in.

Residents weren’t told the full story. The public line focused on “reservoir management” and “long‑term stability”, phrases so vague they slid right past most people’s attention. Flood maps improved slightly. House prices held up. The emergency was, for the moment, contained.

From a technical perspective, the logic is defensible. If your house is quietly sliding off its foundations, you brace it before you debate the ethics. Engineers are trained to solve the immediate risk first, then communicate. Civil infrastructure doesn’t lend itself to mass town‑hall discussions in the middle of a crisis.

Yet cities are not lab benches. They’re made of people who risk their savings on mortgages, who deserve a say when the very ground beneath them becomes a managed experiment. *When water is pumped into rock under your feet without your knowledge, the line between protection and paternalism gets very thin.*

There’s also a political temptation: if subsidence can be slowed underground, pressure eases to confront the harder surface choices — like retreating from flood‑prone zones or rethinking real estate booms built on fragile land.

How transparency could have changed everything

There is a different way this could have played out. Cities could have started with simple, brutal honesty: maps at bus stops showing sinking zones, public dashboards with injection data, school visits explaining the geology under local playgrounds. A kind of “open‑heart surgery” approach to infrastructure.

Technically, that’s hard work. You need translators between engineers and ordinary people, between seismic charts and kitchen‑table fears. You need local media willing to dive into subsidence, not just splashy storms.

Yet the basics are straightforward. Clear summaries of where injections are happening. Plain language about risks, uncertainties, backup plans. And one crucial sentence that rarely appears in official documents: “Here’s what we don’t know yet.”

Belated transparency tends to arrive only when cracks show up on the surface. Literally. Pavement buckling, doors no longer closing smoothly, drains backing up in neighborhoods that never flooded before. That’s when rumors start to run faster than facts.

We’ve all been there, that moment when we realize decisions about our safety have been made in rooms we never entered. People feel managed, not included. Trust doesn’t just evaporate; it curdles into suspicion.

Let’s be honest: nobody really reads every environmental bulletin or technical annex. So when authorities claim, “We published it, it was public,” it can sound like dodging the deeper responsibility to actually speak with people, not just file PDFs on government sites.

“Engineering without consent is always a short‑term solution,” a coastal geologist told me. “You can hold up a city quietly for a while. But if people discover it by accident, every future warning you give — about floods, storms, evacuations — will be taken with a pinch of doubt.”

- Ask the blunt question: Is my city affected by subsidence or underground injection? Local geological surveys, university research labs, and independent hydrologists often publish maps more candid than official brochures.

- Look for **patterns on the surface**: doors sticking across a whole block, repeated pipe breaks, “mysterious” flooding in light rain. None of this proves injection is happening, but it can prompt better questions at city meetings.

- Follow the permits

- State oil and gas commissions, water boards, and environmental agencies usually list injection wells online. The names are dull. The implications sometimes aren’t.

- Push for layman‑level reports

- One accessible annual report, with maps and real language, can do more for trust than a stack of technical appendices.

Living atop a managed experiment

There’s a strange intimacy to this whole story. Most of us will never see the inside of a deep injection well, never touch the rock that holds up our streets. Yet our lives are subtly dependent on those underground choices — how much pressure to add, how far to push, when to stop.

Some engineers argue that secrecy is overstated, that permits are public and nothing truly “hidden” took place. Activists counter that legality isn’t the same thing as legitimacy, that consent is more than a signed line in a regulatory document. Between those positions lies the everyday resident, who just wants to know if their grandkids will inherit a house that still sits roughly where it is today.

The truth is, many of these interventions probably did delay disaster. Some neighborhoods were spared the worst of the sinking. Some storms met city streets that sat a little higher than they otherwise would have. But there is also a quieter cost when people later discover that the stability they counted on was actively engineered out of sight.

| Key point | Detail | Value for the reader |

|---|---|---|

| Subsidence is man‑made | Oil, gas, and groundwater extraction can cause land to sink under cities | Helps you see your neighborhood as part of a deeper geological story |

| Water injection is real | Engineers do pump water into depleted fields to stabilize ground | Gives context when you hear about “reservoir management” or new well projects |

| Trust is part of the infrastructure | Quiet fixes can work technically while eroding public confidence | Encourages you to ask clearer questions and demand transparent communication |

FAQ:

- Question 1Are cities really pumping water underground to hold themselves up?

- Question 2Is this practice safe for drinking water and earthquakes?

- Question 3Why wouldn’t authorities talk about this openly from the start?

- Question 4How can I find out if my area sits on a depleted oil or gas field?

- Question 5What should residents be asking officials about subsidence and injection projects?