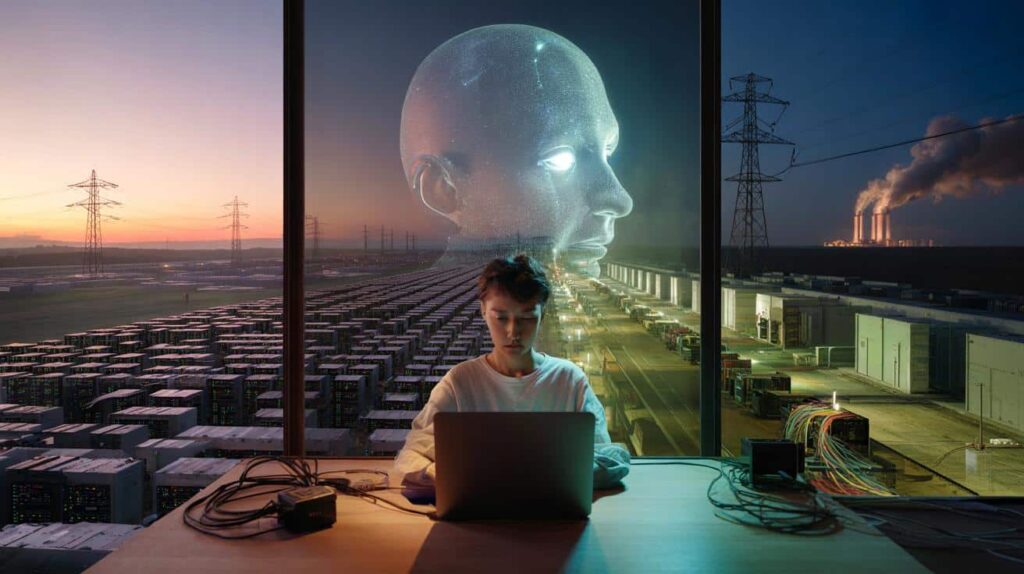

Behind the screen, something far less glamorous is happening.

Artificial intelligence looks weightless: a chatbot in a browser, a feature on your phone, a button in your email app. Yet each AI prompt leans on vast data centres, specialised chips and huge flows of electricity and water. Researchers at MIT are now warning that this invisible infrastructure could reshape global energy and resource use far faster than regulators and planners expect.

AI’s hidden footprint starts with power

The first thing AI consumes is electricity. Not a little, but grid-scale amounts measured in megawatts and terawatt-hours.

Training a modern generative model means running billions of calculations again and again on powerful chips. Once the model is launched, the “inference” phase – all the everyday questions users ask – keeps those chips humming.

Data centres worldwide used around 460 terawatt-hours of electricity in 2022, roughly the same as France’s entire annual consumption, and that figure is on track to more than double by 2026.

In North America alone, data centre power demand jumped from 2,688 megawatts at the end of 2022 to 5,341 megawatts a year later. AI isn’t the only driver, but it is now the main reason new server farms are being proposed in the US, Ireland, the Netherlands and beyond.

The load is not smooth. Training runs create sharp spikes in consumption that grid operators must anticipate. When renewable output is low, these spikes can push utilities to fire up gas plants or even diesel generators, raising emissions at the exact moment the tech sector claims it is going green.

One AI question vs one web search

For users, it feels as though asking a chatbot is no different from a Google search. The energy bill tells a different story.

An average ChatGPT-style query is estimated to consume around five times more electricity than a conventional web search.

As models grow in size and capability, they demand even more computation for each answer. That makes the climate impact heavily dependent on how quickly the energy system decarbonises – and on whether AI demand outruns clean supply.

Water: the other resource AI drains

Electricity is only half the picture. Keeping tens of thousands of chips cool generates a huge thirst for water.

Most large data centres use water-based cooling systems. That water can come from municipal networks, rivers, lakes or groundwater. Each kilowatt-hour consumed by a typical data centre is linked to a significant water use, from cooling towers on site to the upstream water needed for power plants.

Researchers estimate that running a data centre can use around two litres of water for every kilowatt-hour of electricity consumed.

In regions with scarce water or stressed ecosystems, this raises difficult trade-offs between digital growth and local needs. A single new AI-heavy campus in a dry area can compete with agriculture or households for the same limited resource.

Where AI and drought collide

Countries such as Spain, the United States and parts of India are already grappling with heatwaves and falling reservoirs. Placing large AI data centres in these regions can amplify the pressure, especially in summer when both air conditioning and server cooling peak.

- High temperatures mean more cooling, and therefore more water.

- Droughts reduce available surface water, pushing operators towards groundwater extraction.

- Local ecosystems can suffer when rivers and aquifers are drawn down faster than they recharge.

The hardware behind AI’s emissions

Beyond day-to-day operations, the machines that power AI have their own environmental cost. Manufacturing servers and, especially, high-end chips is resource-intensive and highly concentrated in a few countries.

Graphics processing units (GPUs) are the workhorses of modern AI. They are built for parallel calculation and leave traditional CPUs in the dust for training neural networks.

Nvidia, AMD and Intel are estimated to have sold around 3.85 million GPUs to data centres in 2023, up sharply from 2.67 million in 2022, with 2024 likely to be higher again.

Each GPU involves mining and processing metals, intricate semiconductor fabrication and global shipping. Compared with standard processors, top-tier AI chips are larger, more complex and more energy-intensive to produce, which increases their embodied carbon footprint before they ever reach a rack.

Poop From Young Donors Reverses Age-Related Decline in The Guts of Older Mice : ScienceAlert

Poop From Young Donors Reverses Age-Related Decline in The Guts of Older Mice : ScienceAlert

From mines to fabs to landfills

The AI hardware story stretches from copper and rare metals pulled out of the ground to chemical-heavy chip plants and, eventually, to e‑waste.

Pollution risks arise at each step:

| Stage | Key impacts |

|---|---|

| Mining | Habitat destruction, tailings, water contamination, high energy use |

| Chip fabrication | Toxic chemicals, greenhouse gases used in etching, large water and power demand |

| Assembly & transport | Emissions from logistics, packaging waste |

| End of life | E‑waste, limited recycling of advanced components, potential leaching of hazardous materials |

With AI demand surging, data centre operators refresh their hardware more often to stay competitive, shortening the effective lifespan of these complex devices and increasing the churn of materials.

Why MIT says we are still flying blind

Researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology argue that society is underestimating the full environmental cost of AI, largely because the technology is evolving faster than measurement frameworks.

They highlight several blind spots:

- Training data and methodology are rarely published in detail, making it hard to estimate total training energy use.

- Companies often report global emissions in aggregate, without breaking out what is driven by AI.

- Supply chains for chips and servers are opaque, with limited public data on embodied carbon and water use.

MIT scientists say we lack “systematic and comprehensive” methods to track the trade-offs of rapid AI development in real time.

Without better data, policymakers and energy planners struggle to forecast how many new power plants, grid upgrades or water infrastructure projects will be required to feed the AI boom.

Can cleaner energy save AI’s conscience?

Tech giants point to aggressive renewable energy purchases and carbon-neutral pledges as evidence that AI can grow without wrecking climate targets. Reality is mixed.

Many firms buy certificates or fund distant wind farms while still running power-hungry data centres in regions dominated by fossil fuels. When AI demand spikes at night or during windless, cloudy periods, those servers lean on whatever is on the local grid at that moment.

Some promising ideas are emerging: siting data centres near hydro or geothermal resources, coupling them with large batteries, or timing training runs to periods of excess renewable generation. Yet these approaches are far from universal, and they rarely address water use and hardware manufacturing impacts.

What “training” and “inference” really mean for emissions

Two AI terms are worth unpacking, because they relate directly to environmental impact.

Training is the one-off (or occasional) phase where a model learns from massive datasets. This can take weeks on thousands of GPUs, using large bursts of energy and water. For frontier models, training alone can emit as much CO₂ as the lifetime emissions of hundreds of cars.

Inference is what happens every time you type a prompt or a company runs AI on customer data. Individually, each interaction is small. Yet when millions or billions of prompts are processed daily across chatbots, email tools, search engines and phones, the cumulative energy use can rival or exceed training.

If AI assistants become the default interface for everything from office work to streaming recommendations, inference emissions may become the dominant part of AI’s footprint.

What if AI use keeps doubling?

Imagine a scenario where AI queries per person double every year for the next three years, as more services integrate generative tools by default:

- Year one: AI is used occasionally, mainly by early adopters.

- Year two: it is built into office software, search and messaging; daily use becomes common.

- Year three: many apps run AI in the background, generating summaries, alerts and recommendations without a direct prompt.

In that world, even if each AI answer becomes slightly more efficient, total demand could soar. Electricity grids would need to expand, new data centres would be approved more quickly, and local communities could face new competition for land and water.

On the positive side, targeted AI applications might help utilities forecast demand, integrate renewables and reduce waste in other sectors. For example, smarter control of heating, logistics or industrial processes can cut emissions, potentially offsetting some of AI’s own footprint. The balance depends on choices being made now about where AI is deployed and how transparent tech firms are about its true costs.